A genetic analysis of a baby’s remains dating back 11,500 years suggests its ancient DNA belongs to a previously unknown human population in America.

Scientists collected an ancient DNA sample from an infant that died only a few weeks after it was born.

They found it buried at the Upward Sun River archaeological site in Alaska.

The study showed that the baby was part of a group of people who were genetically different from humans in northeastern Asia, the area that began a migration into North America.

Moreover, the study discovered that this group had different genetics, unlike the other two, already known groups of Native Americans.

Life and death in the Americas

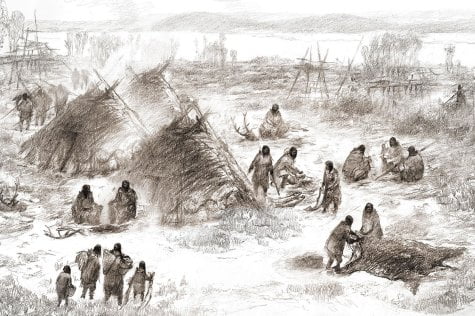

Many years ago, on the place where the baby briefly lived, there was a residential camp. The camp had three tent-like configurations.

The baby girl was buried underneath one of them, together with another female infant.

According to Ben Potter, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks told Live Science that they later found a third child. This one was around 3 years old when it died and it was buried in the middle of the same place.

A burial deep in a hole below the frozen exterior helped to shield the infant’s remains. Alongside, it helped to preserve the functional units of the infant’s ancient DNA and partial DNA from the younger infant.

The study says the two babies were referred as Xach’itee’aanenh t’eede gaay (“sunrise child-girl”) and Yełkaanenh t’eede gaay (“dawn twilight child-girl”) by the native inhabitants.

Some native people there worked together with the scientists into examining the remains and the archaeological site as well.

Potter said that finding remains of ice age people is extremely rare. Populations back in those days were quite movable. They didn’t lodge together in perpetual villages nor created burial spots.

Thus, discovering a site where someone had died and left ancient DNA was a fortunate occasion for the scientists.

“It’s really rare to encounter hunter-gatherer burials — period,” said Potter.

“Another issue is that we’re dealing with some of the earliest people in the Americas, and so there’s an even smaller population to deal with. All of these factors make it difficult to find these [remains], so these are really rare and priceless windows into the past,” he added.

Reconstructing the ancient time

Early accounts of the human arrival in America implies that 15,000 years ago, during the late icy Pleistocene epoch, people passed Beringia and scattered around North America and later South America.

However, modern discoveries revealed the first populations of Native Americans had different genetics from their Asian ancestors 25,000 years ago.

The new ancient DNA knowledge supports the idea of an elongated stay in Beringia.

By the same token, the remarkable discovery of a previously unknown population in Alaska has its own importance.

The group has its own genetic structure and this makes a sudden development of the human migration story.

The study implies that most probably, the genetic split between the ancient Beringians and old Native Americans happened in Eurasia.

With this in mind, the groups likely arrived separately in North America. Furthermore, the study suggests two possible solutions:

Either the groups arrived at the same time through different geographic regions or one after another through the same road.

“This scenario is most consistent with the archaeological record, which to date lacks secure evidence of human occupation in Beringia and the Americas dating to more than 20,000 years ago.

“But it is also possible that the split occurred after a single population was established in eastern Beringia,” the researchers said.

The far north was one of the first locations with modern populations that emerged in Africa.

We still have a lot to discover how our species migrated, adapted and survived in different ecosystems.

Particularly speaking, in the north, the group of ancient Beringians lived from 12,000 to 6,000 years ago. They survived tense natural fluctuations, such as climate change and large animal extinctions.

Not only enduring, they managed to survive without essentially altering their technology. Chiefly, it was based on a unique type of stone tool called a microblade.

“Understanding the adaptive strategies that made that possible — the innovations, the social organization, how people cooperated and how they made their tools — is really a profound way to understand our species,” Potter said.